Hubris, Greed, and Taking Hispanic Voters for Granted

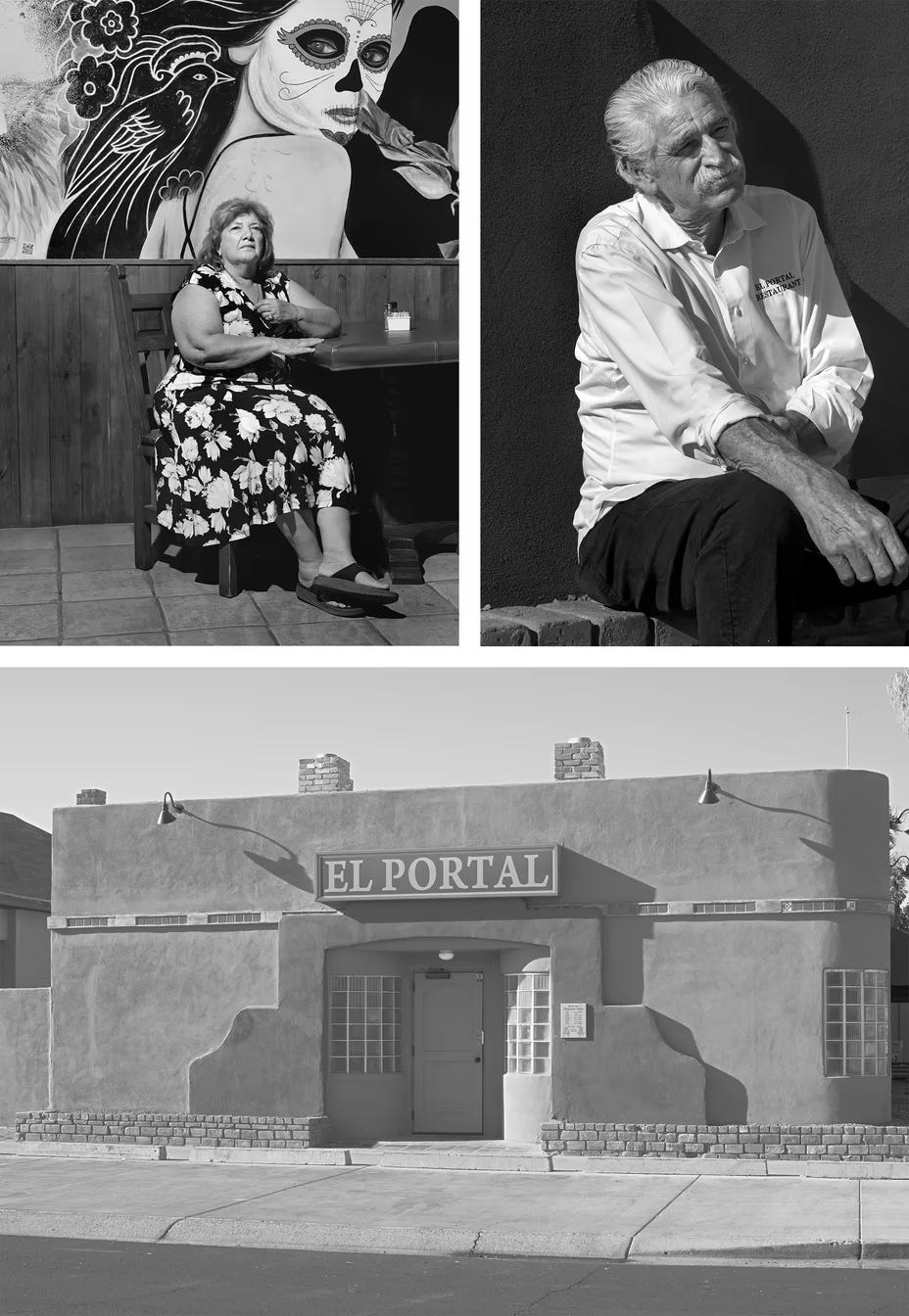

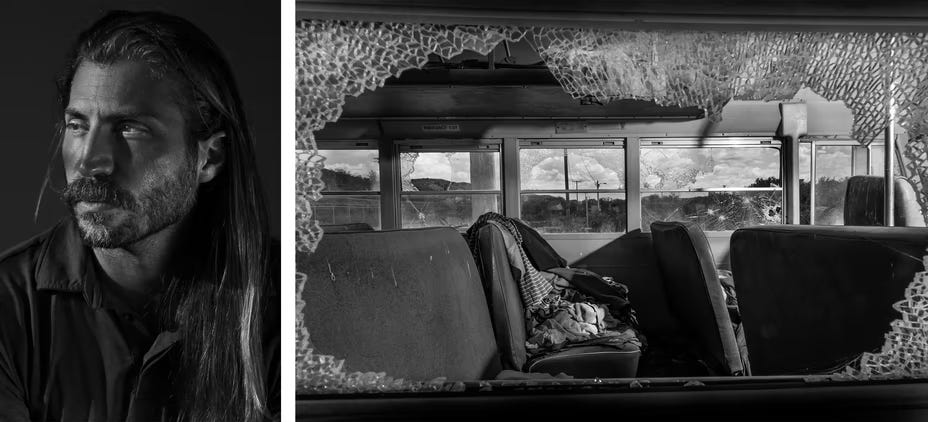

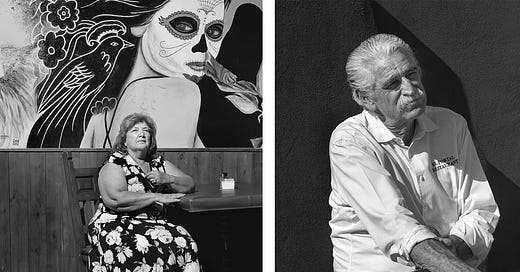

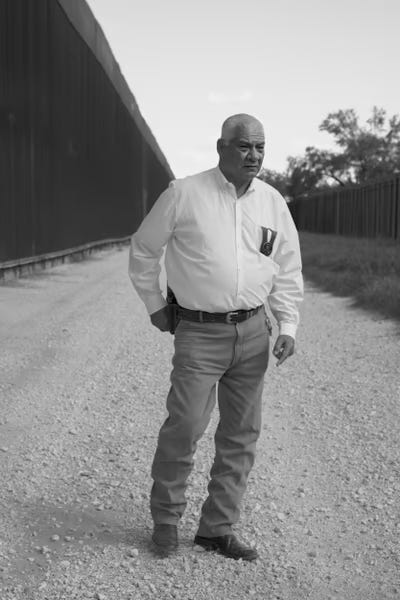

Sheriff Joe Frank Martinez and Former Del Rio Mayor Bruno Lozano in The Atlantic

Good Morning Friends,

This has turned out to be a long newsletter. Possibly too long for gmail to deliver in its entirety. If it cuts off without reaching our customary disclaimer at the end, please find the whole thing on our page at https://thecavalryman.substack.com/

We couldn’t let another day pass without calling your attention to a hot fresh article in “The Atlantic.”

A lot of conservatives dismiss The Atlantic as just another lefty fishwrapper— a partisan publication without even the grace to pretend to impartiality. It’s actually a poor fishwrapper— glossy pages, but we digress. Sometimes writers there strike onto things that deserve a wider audience than the mostly leftward ghetto The Atlantic has constructed for itself.

And so it is this morning, with a piece titled “Why Democrats are Losing Hispanic Voters” by a writer named Tim Alberta.

Have you ever met someone who’s watching their life’s work—their very legacy—fall apart in front of their eyes? I’m talking to two of them right now.

Earl and Mary Rose Wilcox spent the morning juggling plates of chorizo and shouting orders in Spanish toward the kitchen behind them. Now they’re catching their breath in a corner booth at El Portal, the South Phoenix restaurant they’ve run for two decades. They point out the members of their family depicted in a mural on the nearby wall, retracing the mission that brought them to this place and wondering aloud how it all went wrong.

I came to Arizona looking to answer the question of why, over the past few years, so many Hispanics have fled the Democratic Party. This exodus is evident across numerous counties, congressional districts, and battleground states, but the stakes seem highest in Arizona, where Republicans are promoting a slate of extremist candidates and counting on Hispanic voters to help put them in office.

What I found is Earl and Mary Rose, a couple in their mid-70s and the twin bosses of a Phoenix political machine, reckoning with the same awful conclusion I have heard from so many Hispanics, both here and around the country. “The party doesn’t care about us,” Mary Rose tells me. “They pretend to care every two years.”

—Writer Tim Alberta, The Atlantic

We’re not that familiar with Alberta’s scribblings ourselves— a couple minutes of googling shows he’s one of a handful on the left that have been banging a drum about some kind of eventual civil war in the United States recently.

That’s a whole thing that probably deserves another look from us, given this very agile and persuasive article about Hispanic voters and the way they seem to be switching political parties in areas all over the country.

Alberta goes from Miami to Del Rio to Phoenix and elsewhere for this reporting— we’ll mostly excerpt the Del Rio portion, and hope to convince you to click on through for the rest of it.

But to sum it up— Alberta basically constructs an argument that today’s Democrats have lost touch with working class voters and have somehow become the ivory tower party. That is to say— most of their support seems to come from college-educated white liberals with an ivy league leadership cadre at the very top— all focusing on esoteric concerns that have nothing to do with the cost of a loaf of bread or a gallon of milk— major worries for families on the Southside of San Antonio and other places that are all looking for a sign that things are going to get better.

To paraphrase Democrats of yore: “It’s the economy, stupid.” That was 1992. Doesn’t feel that long ago, but it’s been an age.

He also explores how while initial attempts to make President Donald Trump an object of fear for Hispanics in 2016 may have been successful— Hispanic voters have had plenty of time to process those fears and compare them to the reality of what actually happened during his presidency and the reality of current events.

There’s also a section about “Latinx.”

There’s a whole lot in the piece that we don’t want to spoil for you and we hope you’ll click through and discover it.

Let’s skip over to the meat of local concern and Alberta’s visit to Del Rio.

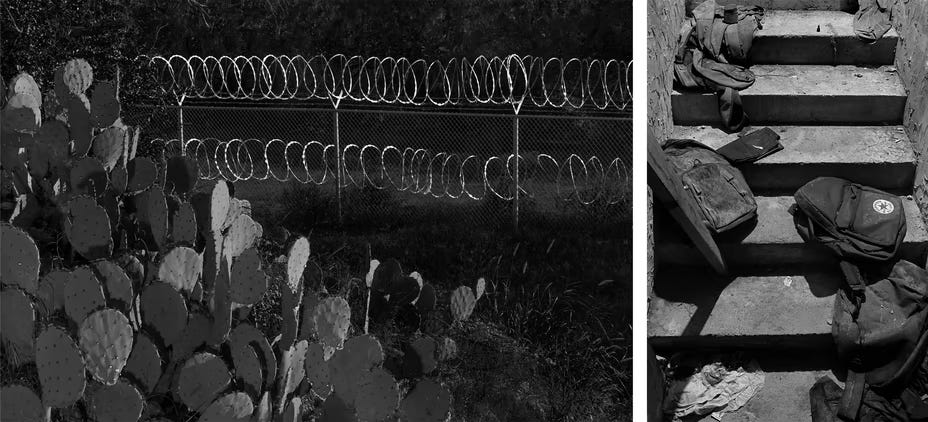

In Bruno Lozano’s blue pickup truck, the air-conditioning whistling through every vent, we stopped and gazed at the Del Rio International Bridge. It was here, Lozano told me, that in September 2021 tens of thousands of Haitian migrants gathered underneath the bridge and set up camp for several days in extreme heat. Del Rio had dealt with migrant waves before, but nothing like this. The city could not handle the influx; its border-processing facilities were at capacity, its humanitarian workers past their breaking point. The community was panicked. Lozano, then the mayor, was desperate. Some of these migrants, he thought, were going to die.

“I’m right here, at the bridge, watching this thing spiral out of control. And Democrats in Washington are like, ‘Nothing to see here,’” Lozano said.

Lozano told me he reached out to every Democratic official he could think of, in Texas and beyond, pleading for any help or resources they could offer. When that failed, he asked them to come visit Del Rio, to at least shine a light on what was happening at the border. “They looked the other way,” Lozano said. “They just pretend it’s not happening.”

When he was elected mayor of Del Rio in 2018, Lozano, just 35 years old at the time, fit the profile of a rising star in the Democratic Party. An openly gay Hispanic military veteran, Lozano “checked every box” for the party. Since he had defeated a Republican incumbent just as his county was beginning to turn red, Lozano said, “you would figure Democrats might listen when I’m telling them something is wrong.”

—Writer Tim Alberta, The Atlantic

For what it’s worth, many around here have been quietly impressed with Mayor Lozano’s performance during the border crisis. Recall, it was during the height of the Haitian event under the bridge that Lozano took the measure of shutting down all international traffic at the Port of Entry— and stood tall doing so in the face of powerful business interests, and great local dismay with many workers in Del Rio frequently crossing back and forth to homes in Ciudad Acuna. Even so— his decision most definitely arrested the attention of federal and state authorities and helped incentivize them to stop with the gaslighting and find a solution quickly.

Lozano said he began sounding the alarm almost as soon as Biden took office. He told his fellow Democrats that, for all the damage done by Trump’s cruel border-security policies, a relaxed approach to border enforcement could prove even more disastrous. He warned them of a potential humanitarian or national-security crisis. He told high-ranking party officials in Austin and in Washington—including during a visit to the White House for an LGBTQ pride event—that Hispanics in his community were turning on the Democratic Party, in part because of its indifference to the chaos at the southern border.

He told me they refused to listen. And today, Lozano said, pulling into the parking lot of a Ramada Inn a few miles from the border, the problem is worse than ever.

The Ramada is where locals host wedding receptions, where businesspeople and politicians meet for breakfast, and where, on a blazing July afternoon, the Del Rio Chamber of Commerce was holding its monthly luncheon. There was no vacancy at the hotel; rooms were booked for Border Patrol agents who had flooded into the area to reinforce a sector that was being overrun.

“This is the biggest wave of illegal immigration in American history, and we’re at the epicenter of it here in Del Rio,” Jason Owens, the Border Patrol’s chief patrol agent of the Del Rio sector, announced at the luncheon. “In the last 24 hours, we’ve apprehended 2,240 people in this sector alone.”

The room buzzed. Forty or so people, local entrepreneurs, most of them Hispanic and many of them lifelong Democrats, exchanged looks of dismay. A few expletives could be heard. Owens wasn’t done.

“In fiscal year 2021, we apprehended nearly 260,000 people in the Del Rio sector. That was more than the previous nine fiscal years combined,” Owens said. “This fiscal year … we are already in excess of 330,000 people apprehended in this sector. Last year was record-breaking; this year, we’ve already shattered it.”

It’s not immediately clear to us when these quotes were taken. But rest assured, unless they were taken yesterday, the numbers have already changed to a ridiculous degree. One also can’t help but note the knee-jerk description of “cruel” border policies. What is cruel, anyway? Permissive twaddle that permits the victimization, torture, and instability we are all seeing? Or straightforward, sensible measures that ultimately serve the greater good?

This is Freshman-level intro to philosophy stuff here, people.

But, Alberta’s trying to reach the audience he has there at The Atlantic.

Because of the known gaps in America’s immigration policy, Owens said, many migrants in this area follow a trail to where they know Border Patrol will be waiting. Those who are allowed to stay in the U.S.—because they are not subject to expulsion, or because they have no criminal record—are typically processed, then detained or released, with orders to appear at a future court date.

Owens said it’s the migrants who go out of their way not to get caught—he cited data from video monitoring suggesting that roughly 140,000 people have crossed unmolested in this sector in fiscal year 2022—who worry him the most. Those 140,000 who got away combined with the 330,000 apprehensions makes for 470,000 illegal crossings from October through July—in the Del Rio sector alone. “And there are nine sectors along the southwest border,” Owens said.

When he opened the meeting to questions, person after person demanded to know how this could be happening, who was to blame, and what they could do to punish the political actors responsible.

“How do you feel,” Sarita Perales, an administrator from the local hospital, asked, “about the Biden open-border policy?”

Owens fought a smirk. “The administration will tell you that the border’s not open,” he replied, eliciting groans from the audience.

Technically, the border is not open. But you wouldn’t know it from spending a few days in Del Rio. People I spoke with down there said they’d never seen anything like the mass of humanity moving across the border since Biden became president. In fairness, apprehensions at the southern border began to rise in the spring of 2020 and continued to climb throughout Trump’s final year as president. But the numbers spiked much higher after Biden took office. It’s difficult to examine the policies of his administration—which, according to the left-leaning Migration Policy Institute, “narrowed the scope of immigration enforcement in the U.S. interior” and “adopted something of a new approach to border enforcement”—and dispute the conclusion that Democrats have made it easier for migrants to attempt and complete an unlawful crossing into the U.S., making a historically bad problem much worse.

This is exactly what Perales, a mother of four, feared would happen. Born in Mexico, Perales came to the U.S. legally when she was 7 years old and became a naturalized citizen in 2017. Her first opportunity to vote in a presidential election was in 2020, and she felt “so disappointed with my choices.” Perales grew up in Del Rio, a place with deep Democratic roots. She has progressive sensibilities on many social issues. She hated some of the hard-line policies of the Trump administration, including the forced separation of families at the U.S.-Mexico border. But the more she listened to activists and elected officials on the left, the more worried she became that Democrats would embrace the other extreme—refusing to secure the border at all.

Perales ended up voting for Trump. Despite disagreeing with him and the Republican Party on a host of issues, she told me, she plans to vote a straight-GOP ticket in 2022, because of the chaos Democrats have brought to her community.

“Where is our respect for laws? Where is our respect for the people already here?” Perales said. “I’m an immigrant; I’m also an American. We are allowing our country to be overrun.”

Studies and polling suggest that Hispanics who entered the U.S. legally tend to be more conservative on questions of immigration. Some progressive Hispanics have bemoaned this, likening it to selfishly slamming shut a door behind you. Perales insisted that she doesn’t feel threatened, economically or otherwise, by new immigrants. She understands the hopeless circumstances that drive so many people from impoverished and conflict-ridden countries to make the journey north. What worries her is the perception of “crossing without consequences.” She wants the U.S. to broadcast a stricter approach to immigration, not just for the sake of the rule of law and for the stability of her community, but also for the well-being of those thinking of coming here.

“They’re being treated so inhumanely,” Perales said of the migrants traveling to America. “But it’s the open-borders policy that is leading to that inhumane treatment.”

Joe Frank Martinez, the sheriff of Val Verde County, told me the same thing when I visited his office in Del Rio. A strong show of deterrence at the border, he said, is the decent thing to do. Not a week went by this summer, Martinez said, that he and his deputies didn’t discover a body of someone who had either drowned in the river or perished in the heat. Shortly before my visit, he told me, they recovered four corpses in the span of three days. (I checked the weather app on my phone. It was 106 degrees outside.)

Like most of the sheriffs in South Texas, Martinez is a Democrat. But definitions are a funny thing down there. Many of the residents have ancestral roots in both old Mexico and present-day Texas; they identify as “Tejanos.” In the same way Tejanos here don’t identify with, say, Mexican Americans in Arizona, Democrats here don’t identify with Democrats just about anywhere else. Martinez is pro-life, pro-gun, and generally conservative in ways that don’t mesh with the modern Democratic Party.

He believes that both parties deserve blame for failing to fix a broken immigration system and “put something in place that can reasonably allow people to make a legal entry.” But, Martinez insisted, this present crisis is one of his own party’s making. “Right now, these migrants feel like they’ve got a standing invitation from this administration to cross the border,” he said.

It wasn’t long ago that Democrats ruled South Texas. Today, Martinez told me, “the Democratic strongholds in Del Rio aren’t real Democratic anymore.” Val Verde County, which Democrats carried by an average of eight points in the previous three presidential elections, went for Trump by 10 points in 2020. The Twenty-third Congressional District, which covers Val Verde, is held by a Republican. Just weeks before I arrived in Del Rio, Mayra Flores, a Mexican-born Republican, flipped the Thirty-fourth District—farther to the east, in the Rio Grande Valley—in a special election. (A Democrat had carried the district by double digits in every election since it was redrawn after the 2010 census.) The GOP is favored to flip the neighboring Fifteenth District next week and represent a majority of Texas’s border districts; less than a decade ago, Democrats controlled every single one.

Martinez said most of the Democrats he’s known over the years have become skeptical of the party. For longer than he can remember, he’s had a weekly breakfast with the same group of seven or eight guys at the Ramada. They were always Democrats—all of them. Now, he said, there’s only one holdout. The rest have switched sides.

In the sheriff’s view—and he said it’s part perception, part reality—his party has become too progressive for Hispanics in a community like his. “This talk of defunding the police, it’s had a real impact,” Martinez said, describing the local Hispanic community as ardently pro–law enforcement. Meanwhile, he added, the moderates in his party at the state and national levels aren’t doing enough to push back on the left. Over the past three years, Martinez estimated, he’s given tours of the border to more than 100 members of Congress. “I haven’t had a single Democrat here. Not one,” he said. “And trust me—I’ve invited them.” (Not long after we spoke, Martinez finally welcomed his first congressional Democrat, Darren Soto of Florida, to the border.)

In Lozano’s truck, as we drove on a narrow road that runs parallel to a stretch of border fence—started by the George W. Bush administration, continued under Obama—he was still seething. Progressives exploit the suffering at the southern border to raise money or get booked on television shows, he said, but they won’t actually come see it for themselves. I asked him why.

“Because it’s a romanticized ideology,” Lozano said. “It’s easy for them to romanticize this whole situation. ‘They’re struggling! They need help! They’re coming here for a better life!’ It’s harder for them to come look at bodies of people who died in 107-degree heat. Kids who drowned. Border Patrol agents—who they’re so opposed to—trying to help pregnant mothers. None of this fits their narrative.”

I asked Lozano what he wants Democrats to do about the border crisis. He laughed.

“Democrats refuse to even call it a crisis. They’re gaslighting me,” Lozano said. He ran through a list of requests: more funding for Border Patrol; better technology to monitor movement; more support for humanitarian groups on the ground; stricter processing policies to deter would-be migrants; and, yes, in certain places, reinforced physical barriers. Above all, he wants Democrats to stop signaling that America has an open border. Throughout the 2020 Democratic presidential primary campaign, he noted, the party’s aspiring leaders took a host of positions—on decriminalizing border crossings, or providing health insurance to undocumented immigrants—that broke with decades of orthodoxy, to appease the progressive base.

“I’m all about the American dream. But this is unsustainable, just totally unsustainable,” Lozano said. “Government is supposed to be about stability. But this party, my party, is inviting all this instability. I’ve had enough.”

Lozano is no longer the mayor of Del Rio. This summer, just a few weeks before I came to town, he served his last day in office. Once a promising young prospect in the Democratic ranks, he quit electoral politics, walking away from a job he loved. Now, he’s thinking about quitting the Democratic Party, too.

—Writer Tim Alberta, The Atlantic

We feel terrible about cutting and pasting so much of Alberta’s article. But we wanted readers to feel satisfied, knowing that most will not click through. We also wanted to avoid being accused of selectively quoting the man or misrepresenting his work. Hopefully lack of a profit motive and principles of fair use will serve as an excuse.

We also must confess to being quite taken with Philip Montgomery’s photos. Someone needs to tell Bruno and Sheriff Joe Frank Martinez to get some copies printed and framed. Both men somehow look like they’ve stepped out of some mythic modern West. And it’s not just the black and white. But we digress.

We’re going to link the piece again here for your convenience and encourage you to give it a read in the Doctor’s office or some other spot where you’ve time. There are whole sections exploring communities in Arizona and Florida with their own tales to tell about why they’re turning red. One area Alberta glosses over, sad to say, is the Rio Grande Valley. While superficially similar to Del Rio, most Texans who’ve visited both locations can attest they are quite different culturally, and it would’ve been illuminating perhaps, to see what he came up with down there.

The article also seems to come across as an admission that we are heading for a red wave this midterm— even before the votes have been counted.

The lessons here for Republicans and others seem pretty simple. Don’t take any voting bloc’s support for granted. And realize that for the majority of folk— no matter the color of their skin— the most important color is green. If no one is making the kind of living they want, and can’t see a path toward doing so, the rest of whatever you’re pushing will eventually have no home.

People need and deserve the promise and potential of their own aspirations. Period. For all the talk of what Democracy is and isn’t and what freedom means— to us here at the Dispatch, that is ultimately what it boils down to. Dream your dreams, and no reasonable law or government will try and stop you. That’s it. That’s freedom, when paired with the most necessary public safety compromises.

We are all of us blessed to be living in a time where the internet and modern technology exists to make so many aspirations seem more possible than ever. Given that, it is mindboggling and dismaying how hopeless and helpless some have managed to make the last few years seem and feel.

People must necessarily reject this. To do otherwise is the spiritual sibling to just laying down and dying.

Early voting ends today.

Election day is Tuesday the 8th.

For some solid analysis of early voting around the state, we invite you to visit a cat by the name of Derek Ryan.

He’s an Austin-based Republican political consultant, but his stuff is pretty bias free and almost entirely focused on the raw numbers as reported by counties around the state.

Here’s his top paragraph summary posted yesterday afternoon:

4,227,631 people have voted. That is 23.9% of all registered voters. Typically, ten days of early voting accounts for 80.4% of all votes cast during early voting. The last two days of early voting account for the remainder, with the Thursday being 7.8% and Friday being 11.8%.

—Derek Ryan, Ryan Data & Research

A lot of voters out there still have yet to vote. If you click through to his work, you can also find a county by county breakdown of numbers. Maybe useful or interesting, or not.

And on that note, we’d like to wish everyone a fantastic weekend. We will definitely not have another newsletter until Monday or Tuesday, unless something absolutely crazy happens around here. “Lord willing, and if the creek don’t rise,” in other words.

As always, this newsletter is an independent work product that predates our employment at the Kinney County Sheriff’s Office, and is kept as separate from that work as possible. It shouldn’t be mistaken for any kind of an official County communication, and any misdeeds, errors, or other issues are entirely our own.

See you soon.

Good article and information. I don't see anything good happening after Tuesday.

Edited to replace "your" with "you're." Ja, ich bin grammar nazi.