Good morning friends,

We didn’t expect to be writing again so soon on the heels of our last dispatch— but somehow, we missed an anniversary of huge local significance.

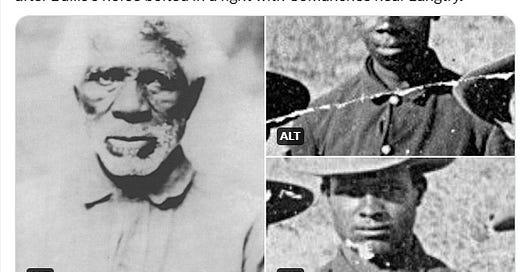

Thankfully, one of our online Texas History associates saved the day, marking it with a post and bringing it to our attention.

If you’re not already following Derrick G. Jeter on twitter or here on Substack (porque no los dos?), you’re missing out on some genuine love for the State and its history.

Pompey Factor, Isaac Payne, and John Ward, as well as fellow Seminole Indian Scout Adam Paine are all buried today in a historic Cemetary site in Brackettville, Texas in Kinney County.

We are told the location houses the most Medal of Honor winners anywhere, outside of the U.S. National Cemetary in Arlington, VA. They elected to be there, instead of Arlington, because that was the place their people lived, and it was important to remain close to them. Down through the years, the Seminole scouts have maintained much of their history and identity as a unique group— a unique people.

We last highlighted the story of the Seminole Scouts and how they found their way to Kinney County, a while back in this past newsletter.

Adam Paine was probably not close kin to Isaac Payne, though both were Seminoles. Adam Paine earned the Medal of Honor in a separate engagement, on another day and is not pictured above. We’ll talk more about him in just a moment.

Pompey Factor was born in Arkansas in 1849, to a Seminole named Hardy Factor and an unknown Biloxi Indian woman. The name Pompey was auspiciously chosen and classically significant, hearkening back to Pompey Magnus of Rome— once one of Julius Caeser’s great rivals in the time of the first Triumvirate, in and around 59 BC. By all accounts, Pompey Magnus was a great soldier and general. Pompey Factor was a private, when he earned the Medal of Honor. We’ll return to his story in just another moment.

Isaac Payne is listed in the records as a “trumpeter” while part of the Seminole scouts, but personally, we find it likely that he didn’t spend much time playing horns, given the Scouts’ specialties and the hard service they saw all across the frontier. Not a lot of room for pomp & circumstance. He passed away at the age of 49 or 50, while living in Mexico after his discharge from the US Army. His remains were returned to the Seminoles at Fort Clark and buried in Brackettville.

John Ward was a Sergeant in the Seminole Scouts. When he was discharged from the army, he spent the rest of his life as a farmer. Living to about 64 or 65, he was also known among his people as John Warrior.

On April 25th, 1875, Ward, Payne and Factor were on patrol near the Pecos River, West of Del Rio and East of Langtry, led by Lt. John Bullis whose own story is almost as notable as those of the men he led.

Indeed, he must’ve been an amazing individual, even as a young Lieutenant, given the events that unfolded on that Spring day along the banks of the Pecos.

Story goes, Bullis and the rest came across sign of Comanche raiders and moved to find and engage them.

In those days, it was common for Comanche to use the area for transit between their stronghold in Comancheria— present day Palo Duro Canyon near Lubbock— to go raiding in Northern Mexico. Mexico at the time was riven with revolution and the northern reaches of the Country were viewed as easy pickings by the Comanche who made their way there every year to plunder all manner of wealth, but mostly horseflesh.

Part of the mission of the Seminole Scouts, and the garrison at Fort Clark in Kinney County was to intercept and halt raiding parties just like this one.

In this case— the men were outnumbered. Something like 25 Comanche raiders were guiding a train of 75 horses.

Interestingly— some sources, including wikipedia say the hostiles were actually Lipan Apaches. It seems entirely possible that it was a mixed group— the Lipan and the Comanche both practiced a lot of the same raiding behaviors. The official Medal of Honor Citation only names them as hostiles.

We spent a few minutes trying to write up a great passage about the battle. But, writer Chuck Lyons at www.history.net already beat us to it:

Bullis and his scouts took cover in some rocks about 75 yards from the American Indians and opened fire.

In the ensuing 45-minute firefight the troopers killed three warriors, wounded a fourth and twice managed to wrest the horses from the Comanches. Finally recognizing that their opponents had flanked them, Bullis ordered his scouts to retreat.

—Chuck Lyons, at History.net

It’s here that we run into another divergence as to what exactly happened. Some say Bullis was knocked off the back of his horse. Lyons writes that he was actually having trouble mounting it to begin with.

Either way, everyone agrees on what happened next.

As they rode off, however, Ward looked back and saw Bullis was having trouble mounting his newly broken horse and was all but surrounded by Comanches.

Ward alerted the other two scouts, and the trio turned to rescue their commander. As Factor and Payne provided covering fire, Ward hauled up Bullis behind him on his own horse and galloped off, abandoning the commander’s frightened horse, saddle and all. All four escaped unharmed, though gunfire had shattered the stock of one of their carbines. Bullis recommended all three scouts for the Medal of Honor, which they received a month later.

—Chuck Lyons, at History.net

While researching this piece— wanting to make sure we got the details and dates correct— we found a great little website— apparently associated with descendants of John Ward. It bears a sincere and heartfelt earnestness as it links the Seminole Scouts with the larger, distinct body of African-American frontier fighters that the Indians named “Buffalo Soldiers.”

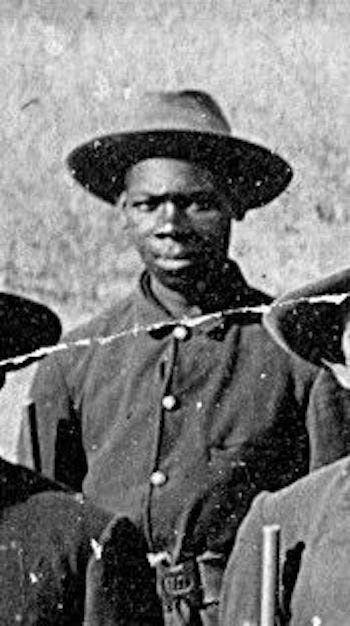

It includes many spectacular photos— including some taken in Kinney County, like this one:

There’s also this one, a rare scene from the Seminole village, as it was, way back when on the grounds of Fort Clark.

Also of note from that same website: A pdf of a typewritten transcription of the letter Bullis wrote to his superiors— describing the incident in his own words:

The truth is, there were twenty-five or thirty Indians in all; and mostly armed with Winchester guns, and they were to (sic) much for us. As to my men, Sergeant John Ward, Trumpeter Isaac Payne, and Private Pompey Factor, they are brave and trustworthy, and are each, worth a medal, the former of which had a ball shot through his carbine sling, and the stock to his carbine shattered. Relative to the Indians, I would say, in my opinion, they were Comanches, and were from Mexico.

After the fight we marched about twelve miles and went into camp at Paint Creek, grass and water plentiful and good. We marched this day fifty-six miles. The following morning (the 26th Instant) we left camp at sunrise and took the main road to Fort Clark where we arrived at 3 p.m.; we marched this day forty-three miles. Total distance marched three hundred and twenty-six miles. I remain, Sir, Very respectfully, Your obedient servant John L. Bullis 1st Lieutenant, 24th Infantry Commanding Scouts

—Lt. John Lapham Bullis

Also included in the PDF, are comments made by Lapham’s superiors, passing them on to others:

Words commendatory of the energy, gallantry, and good judgment, displayed by Lieutenant Bullis, and the courageous and soldierly conduct of the three scouts who composed his party are not needed. The simple narrative given by himself explains fully the difficulties and dangers of his expedition. His own conduct, as well as that of his men, is well worthy of imitation, and shows what an officer can do who means business.

—By Order of Brigadier General Edward Ord, J.H. Taylor, Asst. Adjutant General

Imagine the fortitude it must’ve taken. The split-second decision making, to turn back into the teeth of looming disaster in rescuing Lt. Bullis. As it happens— that heroism would pay future dividends, many years later when the Seminoles encountered friction with settlers in Brackettville.

We promised a closer look at the story of Adam Paine as well.

Paine was a Seminole Scout attached to the body of soldiers traveling under the command of Ranald S. Mackenzie at the battle of Palo Duro Canyon.

The newsletter took a closer look at Mackenzie’s story in this past Dispatch, after some material about the then-present state of Title 42.

Paine helped the cavalry immobilize the camp. The soldiers and scouts took and destroyed 1,400 horses and well as massive amounts of camp equipment and supplies. After the battle Colonel Mackenzie recommended eight of his white soldiers for the Medal of Honor along with Adam Paine.

Paine was discharged from the Army on February 19, 1875, at Fort Clark, Texas. He was awarded the Medal of Honor eight months later on October 13. Paine worked as a teamster for the U.S. Quartermaster Department at Fort Brown, Texas in retirement.

—U.S. National Park Service

Mackenzie has a great quote on the subject of Paine, saying he had the most “cool daring” of any scout he’d ever known. One imagines the curious turn of phrase to describe what seems to be an amazing amount of level-headedness during the stress of combat. The official citation only says he rendered invaluable service to Mackenzie during the engagement at Palo Duro Canyon. But one can find accounts that describe him as exhibiting “habitual courage.”

Sadly— Paine is perhaps most remembered today for being party to the only known instance of one Medal of Honor recipient killing another also bearing the same honor.

Claron Augustus Windus, an Anglo, originally from Wisconsin, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions against the Kiowa in North Texas. He was working as a Deputy Sheriff in Kinney County on New Year’s Eve in the 1870s, when witnesses say he shot and killed Adam Paine— possibly blasting him from behind with both barrels of a shotgun.

At the time, Paine was wanted— accused of stabbing a white cavalry soldier in the heart on Christmas Eve, down in Brownsville. Story goes, he was hanging out with a noted cattle thief named Frank Enoch, who ranged all along the border.

That New Year’s Eve, Paine was back in Brackettville, visiting his people. For this, we return to History.net

Learning that several fugitives would be at the holiday party, Sheriff L.C. Cromwell showed up with Deputy Claron Windus. Three MOH recipients—Paine, Payne and Windus—were now at the party, but not to discuss past accomplishments.

What triggered the violence that rang in the New Year is uncertain. Perhaps Paine and friends simply resisted arrest, or perhaps Windus shot first and asked questions later. What is certain is that Windus’ close-range, double-barreled blast killed Paine instantly. Some accounts say the shot was to Paine’s stomach, while at least one writer claims Paine got it in the back. Windus also mortally wounded Enoch, either with his shotgun or a revolver. In the confusion Isaac Payne and ex-scout Dallas Griner grabbed two horses (apparently not their own) and headed for the border. Payne spent time in Mexico but within the month returned and re-enlisted as an Army scout.

Windus suffered no legal repercussions from shooting Paine and Enoch, and less than a month after the 1876 New Year’s Day fray he gave up his deputy sheriff position to become the Kinney County tax assessor. A month after that he married Agnes Ballantyne, daughter of James B. Ballantyne, county inspector of hides and animals. As tax assessor Windus had advance knowledge of property to be sold for delinquent taxes, and over the years he used that information to become one of the largest property owners in Kinney County. The wealthy Windus boasted the first house in Brackettville with indoor plumbing.

In 1898 the 50-year-old Windus reentered service as a captain and followed Teddy Roosevelt to Cuba. After a year of fighting in the Spanish-American War, he returned to Brackettville in 1899. Windus lived comfortably in Texas until falling ill on September 20, 1927, possibly a recurrence of the malaria he’d contracted in Cuba. He died in the hospital at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio that October 18. Windus is buried in Brackettville’s Masonic Cemetery, some three miles from the burial ground of the four black Seminole scouts who also received the Medal of Honor.

—Writer Don Blevins, at History.net

One detects a few whiffs of what must have been a complicated history for the Seminoles in the early life of Kinney County, as much of the wild-hearted frontier existence started to recede, to be replaced by taxes, rules, surveyors, more taxes, more regulations, and the expectations of new residents in the area who didn’t know or didn’t care about yesterday’s sacrifices and debts of honor and respect.

One finds mention that some at the time in Kinney County viewed the Seminoles as little better than common thieves. The scouts’ families lived as they always had, on land set aside for them by the U.S. Army at Fort Clark. And sometimes, we are told, they’d supplement their diet with some of the cattle roaming the area. Well, sometimes the definition of roaming also apparently encompassed livestock that was owned by local ranchers.

Enough of a hue and cry was raised— including retributive demands, one assumes— that former Lieutenant John Bullis was contacted in San Antonio. Bullis would eventually become a General— can’t remember what rank he held at this precise moment in time— but he reached into his own pockets and paid off the ranchers, in the name of the Scouts and soldiers he’d once led. Bullis had become a wealthy man— investing in a silver mine, alongside General Shafter, who replaced Mackenzie in command of Fort Clark at one point prior.

One imagines it as a particularly gallant act, given what must have been the tenor of the times. One also imagines Bullis would have probably deadpanned and downplayed it.

Interestingly— Bullis was so loved and respected while at Fort Clark and in Kinney County, that the residents of the place gifted him with a pair of ceremonial swords— one gilded, one silvered on his departure from the region. The blades are on display inside the Witte Museum in San Antonio.

It must be noted that the early history of Kinney County and Brackettville was a checkered one. Much of the town during those frontier days could’ve been described as a vice pit.

Merchants and entrepreneurs were keen to separate bored soldiers at Fort Clark from their pay. Most commonly, that meant whiskey, women (prostitution), and gambling. Some journals of the time, charitably described it all as “the liveliest little ‘burg.”

Anyway— that should do it for now. Descendents of the Seminole scouts live in Brackettville and Fort Clark to this very day— maintaining the history and the spirit of their forebears, including a museum on the West side of town. The building itself is a unique spot. Our understanding is that it was constructed by a German immigrant, who had dreams of brewing awesome beer, using the good water that can be found in the area’s wells and springs. Sadly— his designs were predicated on his entire family following him to Kinney County.

They elected not to do so. Family, right? Sheesh.

The building has been a school during and after segregation. We spent at least a portion of our Kindergarten year there. It was a pretty rad spot. No big kids. Spooky grounds, perfect for Halloween. Us 5-year-olds loved it.

The date has caught us off guard. We’ve been meaning to get out to the cemetery and the museum to take our own photos for months now, but here we are— lucky to have found photos others have taken in our own backyard as we scramble to mark this locally significant date.

Mea Culpa.

God Bless Texas. God Bless the Seminoles and the memories of these men, whether good, bad, or simply just complicated.

As always, this newsletter is an independent work product, produced without oversight by any Kinney County officials, and should not be mistaken for a formal communication of any sort.

Thanks for bearing with our ramblings once again this morning— we’ll be back again soon enough, with our regular focus on the current border crisis.

Excellent article.

Edited to Correct: Claron Windus was from Wisconsin, not Kansas.